When Joe Hill Suffered Tuberculosis

Guest post for the Joe Hill Organizing Committee.

Guest post for the Joe Hill Organizing Committee.

It’s a bleak, early spring day in Stockholm, year 1900. A young man has just gone off the train from Gävle. Outside the Central Station he attracts some attention, not for his youth, not for his slender figure, but for the rashes that cover his face and neck. Is it something contagious? Not leprosy, right?

His name is Joel

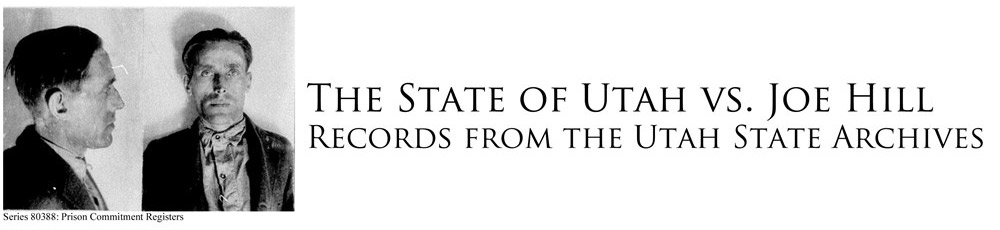

His name is Joel Hägglund (1879 – 1915). A few years later, in America, he’ll take the name Joseph Hillström. After yet another few years his name will be Joe Hill, and he will go down in history under that name—as an agitator, union leader and singer-songwriter. In the year 1915, he’s executed in America, convicted.

With this, the labor movement got a martyr, and this year is the centennial for Joe Hill’s execution.

This agitator, whose songs were sung and whom many sang about on the other side the Atlantic ocean—for example, Woody Guthrie and Bruce Springsteen—has a well-preserved legacy, maybe more in America than in Sweden. Stephen King gave a son the name Joseph Hillstrom, which the son shortened to Joe Hill. On social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, comments are flooding in about the death sentence and comparisons between now and then.

The centennial could just as well be a multi-centennial on the discrimination of people on the edge of the labor market. Today’s unprotected guest workers in Stockholm and other cities have a lot in common with the so called low-skilled work force that Joe Hill wanted organized in the IWW, Industrial Workers of the World.

This organization is described like this by one of Kerstin Ekman’s characters in Menedarna (1970):

“The IWW is something they founded to get a union that also works as a place for the trash. Those who don’t want to educate themselves and would rather not do anything at all.”

The agitator was sentenced and executed in the Mormon state Utah. The U.S. President appealed for a pardon for Joe Hill. The pardon was rejected and the radical Swedish American moved on to the afterlife for what was probably a miscarriage of justice.

The rashes brought Joel to the capital

But let’s move on to the stay in Stockholm. The rashes brought Joel to the capital. The disease symptoms were already apparent in the mid-1890s. He first sought medical attention in his hometown for the rashes on his right hand and one of the alas of the nose. He went to the hospital when they didn’t heal and was treated with x-rays. The diagnose was cutaneous tuberculosis. He quickly went home with a bandage around his hand and a referral to a specialist in Stockholm, Dr. Tage Sjögren on Hamngatan. Sjögren, medical doctor working on a Battalion aid station with skin diseases as a speciality, used phototherapy (or light therapy). Back then this was a new method.

Two to three times a week, Joel had to lie down on an examining table and reveal his skin for the ultraviolet light from a lamp.

“Watch your eyes!”

After the doctor’s or a nurse’s orders, the light was turned on. It’s not difficult to imagine how Joel would rather have his eyes closed than protect his eyes with patches previously used by other patients.

When health wasn’t a hindrance, this soon-to-be revolutionary labor singer hurried out on the streets of Stockholm. With rising restlessness, he waited for the treatment to stop. In the end, he made a virtue of necessity, which already was a saying back then. He started to look forward to the hospital visits, where he had to lay still—which could be healthy for both mind and body.

Hospital care was required

His condition did not improve. Eventually, hospital care was required.

April 15, 1900, Joel was hospitalized in “Serafimerlasarettet” for cutaneous tuberculosis. Forearm and nose glands in particular.

He was treated with phototherapy again, as well as medicines and surgery. Joel was periodically very weak. Friends to his family who came to visit had a hard time talking to him as he was covered in bandages.

The doctors were still hopeful. The youngster’s lungs were strong and the tubercles didn’t seem to reach them.

Serafimerlasarettet, founded in 1872, is usually described as Stockholm’s first hospital and was used until 1980. The buildings on Hantverkargatan on Kungsholmen, opposite the city hall, are still there. Joel’s records were, unfortunately, cancelled after a while, according to the National Archives.

Naturally, the patients didn’t have their own rooms but lay in beds in big hospital wards.

Many patients were workers. Joel laid and listened to wheezing and throat clearing from the patients in the other beds. Some found each other in obvious topics—such as sharp condemnations towards injustices and repression.

When he wasn’t in agony and weakness, Joel participated in the conversations. Otherwise, he laid and stared up at the ceiling. At this point, fight songs from religious melodies started to materialize.

His home in Gävle was pious, but his relationship to God was, with today’s vocabulary, flexible. His grade in Christendom was a C, and one of his most famous songs is about how “you got pie in the sky when you die”.

For two years, he resided in Stockholm

Most of the time, Joel was a lodger on Västerlånggatan in Gamla Stan (the Old City). For two years, he resided in Stockholm. Longer than planned. This was because the treatment took longer than the doctors thought. It was more expensive than Joel’s family expected as well; the hospitalization costed about 75 Swedish öre per day. The family payed, at least initially.

Afterwards, Joel had to pay with what he earned from his temporary jobs. He called himself an ironworker, but he also worked as a paper salesman. Paper salesmen were often seen on the street, young boys in their characteristic hats handed out papers such as Stockholms Dagblad and Stockholms-Tidningen. Joel with his hat might have had a hard time reconciling with both the informal headgear and the often defencist messages in the columns.

Many of the newspapers at the turn of the century, on the other hand, propagated for something as sympathetic as equal and universal suffrage.

He had his political sympathies

Joel was not a searching young man but was clear early on about where he had his political sympathies. Already in Stockholm, he identified as a revolutionary syndicalist and had contact with radical publications such as Brand. When he wasn’t in the hospital, Joel spent evenings at cafés and in parks. Among the new friends were young social democrats who later would become active anarchists or syndicalists.

May 1st started to be celebrated as a labor movement’s worldwide day for demonstrations in the year 1890. Naturally enough, there are no documents that show whether Joel demonstrated or was in the hospital May 1st ten years later. But, wherever he was, he would have agreed with slogans against the throne, sword, and altar. According to a biographer, Ingvar Söderström, was Joel radicalised in Stockholm. The distress and poverty was greater than in Gävle.

His family dispersed

When both his parents were dead, his family dispersed. Out of the nine kids, six survived their first years and grew up. Four sons and two daughters. One son, Ruben, moved to Stockholm. Another brother, Paul, went along with Joel to America. While Joel became a hero in Sweden and America, Paul became the exact opposite. At least in Gävle. This was because he had left his wife and kids.

Paul was married and, a few years later he remarried in America, without divorcing his first wife, says one of Joe Hill’s relatives, namely Rolf Hägglund, who is the grandson to another one of Joe Hill’s brothers, Efraim.

Rolf lives in Västerhaninge. When I take the shuttle train there, it feels like I’m in “Joe Hill-land”. In the centrum, the atmosphere is tough. Many of the unemployed could become members of a modern day counterpart to the militant IWW. On the pub’s patio, some regulars are shivering. And, it was in Västerhaninge that the Mormons built their first Swedish temple.

We talk about how Joe Hill was sentenced to death for murder and executed. A shopkeeper, J.M. Morrison, and his son had been murdered the 10th of January year 1914 in Salt Lake City in Utah. Joe Hill, early suspected for the murder on the shopkeeper, refused to tell the police what he had done that dire evening.

“They have nothing on me”, he said time and time again in his cell, a line that’s repeated in Kerstin Ekman’s work.

Hägglund cherishes the memory of the historical relative

Hard to know why he kept quiet. I believe that the explanations are 25% honor and 75% naïve belief in the judiciary. He couldn’t believe that he was going to be sentenced, since he was innocent, says Rolf Hägglund, who cherishes the memory of the historical relative.

Hägglund’s five kids did their special projects about Joe Hill. So did also two of their cousins. The fact that there are no personal documents left from his time in prison, Robert calls a “historical misdeed”.

For a period, the prison sent Joe Hill’s letters, drafts of song lyrics and other documents to a relative in Sweden. Their widow later burned everything, completely fixated to eradicate the traces of a condemned and executed member of the family.

October 5th it was time for Joel to leave Stockholm and return to Gävle. He walked with some toil towards the central station, made a stop in Järnvägsparken and looked at the statue of Nils Ericson, an engineer but above all railroad worker, just like Joel’s dad, who died after an accident at work. When Joel was only eight years old, his dad who was a conductor, fell under a moving railroad car. He later died from the injuries, one of countless of people who die at work without getting a memorial.

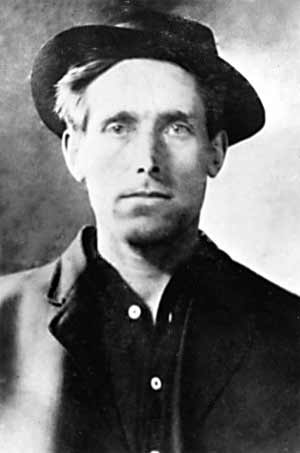

Just as he arrived to the station, the lanky man attracted some attention. His rashes were gone but were replaced by scars. The nose was as thin as a line, one of the alas thin as a leaf, which has been observed by many late beholders of his portrait.

Martyrs’ looks and charisma usually cause endless associations. This was also the case with Joe Hill. But what survived the illness and poverty—indeed, survived death—is above all the songs.

In that sense, a monument has also been erected of a working “Hägglund”.

Jan-Ewert Strömbäck

journalist and writer, Stockholm, Sweden

Translation from Swedish: Dan Strömbäck

Are you interested in publishing your writing on Joe Hill? Write to us and let us know. We welcome your writing and artwork.

Joe Hill and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

Guest post for the Joe Hill Organizing Committee.

Guest post for the Joe Hill Organizing Committee.

Hill and Flynn

From his jail cell, the condemned prisoner Joe Hill began a lengthy correspondence with fellow worker and IWW organizer extraordinaire Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. Despite being railroaded onto death row with the slightest of evidence, the letters between the two legendary IWW leaders reveal Hill’s enormous humanity and generosity—placing humor and concern towards his fellow workers above his own situation.

“We’ve had girls before, but we need some more.”

A month before Hill’s first letter to Flynn, Hill had mentioned Flynn’s effectiveness at organizing women into the IWW. He mentioned Flynn in a published letter in the IWW magazine Solidarity, where he stated that the union needed to be more inclusive of women workers since “they are more exploited than the men.”

Hill wrote of the “sadly neglected” women on the West Coast that the IWW had not reached and “consequently we have created a kind of one-legged, freakish animal of a union,” and he urged the IWW to use Flynn solely for the goal of recruiting more women organizers into the IWW.

When Flynn received her first letter from Hill in January 1915, she was an internationally and nationally recognized public figure. Her ten years work for the IWW had Flynn leading the historic free speech campaigns in Spokane, Washington, and Missoula, Montana, and organizing the great textile strikes in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912 and in Paterson, New Jersey, the following year.

Flynn for the OBU

Flynn was an exceptional high school student in the Bronx, and, much to the disappointment of her teachers and parents, when she was seventeen years old, Flynn left high school before she graduated to empower the disenfranchised into the IWW.

The IWW was the ideal choice for Flynn. A restless soul herself, Flynn enjoyed her life on the road with the Wobblies. The IWW, unlike the recently formed American Federation of Labor, IWW organizers were committed to their vision of OBU (One Big Union) and consistently practiced solidarity: “If you are a wage worker, you are welcome. . . . The IWW is not a white man’s union, not a black man’s union, not a red man’s union, but a workingman’s union.” The AF of L initially focused only on skilled labor workers and avoided women and people of color; the AF of L holding on to the incorrect premise that such workers could not be organized.

When Flynn was sixteen years old, she stepped up to the soapbox and delivered her first speech in Harlem, “What Socialism Will Do for Women.” Flynn possessed an innate brilliance and delivered her oratory easily. With her long black hair, petite frame and blue eyes, Flynn was a striking jawsmith and a vision to behold. Much to the dismay of the local politicians and the local law enforcement, who were always at the ready to squash any Wobbly assembly, wherever or whenever, Flynn stepped onto the soapbox. She drew the biggest crowds ready to hear her message of empowerment. Before long, the Los Angeles Times described her as a “leather-lunged hellion that breathed reddish flame,” and a “she-dog of anarchy.” By the time Flynn would step down from the soapbox, a Philadelphia reporter stated that “the perpetual inebriate forgot about the swinging doors” and “the corner loungers stood straight.” Flynn’s jawsmithing was legendary and remained one of her most effective organizing strategies.

Writing with The Rebel Girl

After Hill’s first letter to Flynn on January 18, 1915, they became regular correspondents. Hill was astounded by Flynn’s prodigious ability to perform a great many tasks within her days and complete them so competently. She was a full-time labor organizer as well as a divorced woman and single parent to a six-year old son. “Have been trying to figure out how you can have the time to write me such nice, fat letters and hold big meetings every night besides,” Hill wrote in a letter to Flynn in March, “but I guess you are like Tommy Edison, you don’t sleep more than four hours a day and work twenty.” In another letter, Hill imagined seeing Flynn “boil spuds, iron clothes, and sling ink all at the same time.”

After Hill’s first letter to Flynn on January 18, 1915, they became regular correspondents. Hill was astounded by Flynn’s prodigious ability to perform a great many tasks within her days and complete them so competently. She was a full-time labor organizer as well as a divorced woman and single parent to a six-year old son. “Have been trying to figure out how you can have the time to write me such nice, fat letters and hold big meetings every night besides,” Hill wrote in a letter to Flynn in March, “but I guess you are like Tommy Edison, you don’t sleep more than four hours a day and work twenty.” In another letter, Hill imagined seeing Flynn “boil spuds, iron clothes, and sling ink all at the same time.”

A month after his first letter to Flynn, Hill began to compose “The Rebel Girl” in appreciation of Flynn’s work and with the hope that the song would “help to line up the women workers in the OBU [One Big Union].” Hill would later acknowledge to Flynn that, given her great influence on him, when he composed the song, “you were right there and helped me all the time.”

Forty years later, Flynn would use the song’s title for her autobiography, The Rebel Girl.

A Visit with Joe Hill

In May 1915, the Rebel Girl Gurley Flynn was able to arrange a visit with Hill, when she would be lecturing on her first national tour since her son was born. It was an ambitious trip: Flynn would be lecturing in forty-seven cities over nineteen states, but it was her May 6th meeting with Hill that was her most anticipated stop.

Previous to meeting Hill, Flynn held some optimism that Hill would eventually be exonerated from this “crude frame-up” given the flimsiness of the evidence the state used to convict him.

The visit would be for only one hour, to be held in the sheriff’s office with others present. Flynn would be his first visitor since his sentencing. Writing about her visit with Hill in Solidarity magazine, Flynn was struck by the juxtaposition of the beauty of Salt Lake City’s streets “with its windswept streets. . . green shimmer, high altitude and clear pure air” against the rank odors of the “fetid jail odor,” cut by the “sickening smell of disinfectants.” They were denied even the smallest pretense of privacy.

It would prove to be their only visit. “He is tall, good looking, and naturally thin after sixteen months in a dark, narrow cell, with a corridor and another row of cells between him and daylight, and ‘nourished’ by the soup and bean diet of a prison,” Flynn wrote in Solidarity.

It would prove to be their only visit. “He is tall, good looking, and naturally thin after sixteen months in a dark, narrow cell, with a corridor and another row of cells between him and daylight, and ‘nourished’ by the soup and bean diet of a prison,” Flynn wrote in Solidarity.

Flynn called Hill a “free spirit” and “inimitable songster and poet of the IWW.” Flynn wrote of their meeting, “Let others write their stately Whitmanesque verse and lengthy, rhythmic narrative. Joe writes songs that sing, that lilt and laugh and sparkle, that kindle the fires of revolt, in the most crushed spirit and quicken the desire for fuller life in the most humble slave.”

Hill retained true to his characteristic trait of deflecting attention away from himself and had Flynn talk at length about the IWW’s progress. “And so the hour was spent in giving him the news of the movement,” she wrote. “I’ve seen men more worried about a six months’ sentence than Joe Hill apparently worries about his life. He only said: ‘I’m not afraid of death, but I’d like to be in the fight a little longer.’”

Flynn was noticeably shaken when their hour had nearly run itself through. She felt as though she was leaving a tomb and thought about Hill’s prospects when the state of Utah was determined to have Hill executed.

When they said their good-byes at the barred door, Hill pointed outside to “an expanse of a beautiful lawn” and attempted a joke about the brevity of his own life. “He’s lucky, Gurley. He’s a Mormon and he’s had two wives and I haven’t even had one yet.”

Fight for Freedom

Back in New York, Flynn worked with Big Bill Haywood in Chicago and IWW writer Ed Rowan in Salt Lake City on Hill’s appeal, to educate and agitate the people on the travesty of justice in Hill’s case. In the coming few months of Hill’s life, as he was becoming more of a symbol than a real man, and, noticing the rapid use of the IWW’s diminishing resources, Hill had urged the IWW through a letter to Flynn to have the IWW cut short their work on his behalf. Hill had wrote that it was senseless “to drain the resources of the whole organization and weaken it fighting strength just on account of one individual.”

While acknowledging Hill’s concerns, Flynn and hundreds of thousands of people would not allow themselves to let Hill remain a condemned man while they were able to fight for him.

Flynn remained his strongest champion. With only forty-eight hours before Hill’s execution date, she had presented Hill’s case to President Woodrow Wilson. Flynn had contacted friend and colleague Edith Cram, a Democrat of high social status and political connections—her husband was the “fixer” for the boss of New York’s Tammany Hall political machine. Cram and Flynn had been granted an interview with Wilson’s private secretary, Joseph P. Tumulty. The secretary had suggested a protocol-breaking plan of having the Swedish Prime Minister issue an appeal to Utah’s Governor Spry on behalf of its Swedish citizen, Joe Hill. He would also forward the appeal to the President himself.

That night, while Flynn and Cram were conferring about the case, the warden of the Utah State Penitentiary placed Hill under a death-watch after his announcement that preparations for the execution had been completed.

When the appeals from the Swedish Prime Minister Ekengreen and President Wilson went ignored by Utah’s Governor Spry, and, after a deluge of telegraphs to President Wilson, Flynn and Cram were given an audience with the President inside the Oval Office. Cram’s husband, John Sergeant Cram, and her brother-in-law, Gifford Pinchot, former chief of the U.S. Forest Service, accompanied them.

“The president greeted us cordially, in fact, he held Mrs. Cram’s hand,” Flynn recalled in The Rebel Girl. President Wilson listened “attentively” and recalled the failed intervention at the request of the Swedish Minister. Wilson wondered “if further insistence might do more harm than good.”

“But he’s sentenced to death,” Flynn interjected. “You can’t make it worse, Mr. President.”

Joe Hill’s Last Night

After the President’s final appeal to Governor Spry’s humanity was denied, Hill wrote again to Flynn, his humor and courage shining through as he faced death alone in his cell:

“Well Gurley I guess I am off for the great unknown. . . . They can kill me I know, but they can never make me ‘eat my own crow’. . . . I would like to kiss you Good-bye Gurley, not because you are a girl but because you are the original Rebel Girl.”

He also thanked Flynn for the photograph she had sent him of her son and told her of the song he had written for him. “You certainly have a right to be proud of your boy,” Hill wrote, “He’s got a forehead like old Shakespeare himself.”

Hill telegrammed Flynn on his last night:

“And now, good-bye Gurley dear. I have lived like a rebel and I shall die like a rebel.”

At ten pm, just before he fell into a heavy sleep, and, thinking that the bluntness of the telegram wasn’t enough, he wrote Flynn his last thoughts:

“I have been saying Good Bye now so much now that tit is becoming monotonous but I cannot help to send you a few more lines because you have been more to me than a Fellow Worker. You have been an inspiration and when I composed The Rebel Girl you was right there and helped me all the time. . . . With a warm handshake across the continent and a last fond Good-Bye to all I remain Yours as Ever.”

The next morning, Hill was executed. Hill’s invited visitors, Ed Rowan among them, were not given access inside the prison as Hill had requested. Hill’s visitors stood outside the prison walls and heard the firing squad carry out their orders.

Ed Rowan immediately telegraphed Flynn in New York:

“JOE HILL SHOT AT SUNRISE. HE DIED GAME.”

Nancy Snyder

Recording Secretary Emeritus, SEIU Local 1021

Are you interested in publishing your writing on Joe Hill? Write to us and let us know. We welcome your writing and artwork.