Guest post for the Joe Hill Organizing Committee.

Guest post for the Joe Hill Organizing Committee.

Hill and Flynn

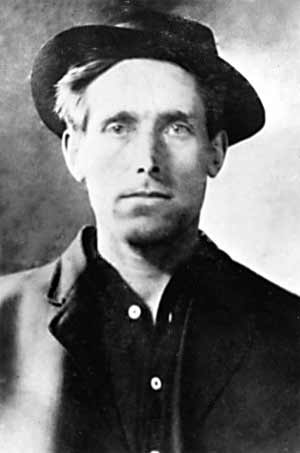

From his jail cell, the condemned prisoner Joe Hill began a lengthy correspondence with fellow worker and IWW organizer extraordinaire Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. Despite being railroaded onto death row with the slightest of evidence, the letters between the two legendary IWW leaders reveal Hill’s enormous humanity and generosity—placing humor and concern towards his fellow workers above his own situation.

“We’ve had girls before, but we need some more.”

A month before Hill’s first letter to Flynn, Hill had mentioned Flynn’s effectiveness at organizing women into the IWW. He mentioned Flynn in a published letter in the IWW magazine Solidarity, where he stated that the union needed to be more inclusive of women workers since “they are more exploited than the men.”

Hill wrote of the “sadly neglected” women on the West Coast that the IWW had not reached and “consequently we have created a kind of one-legged, freakish animal of a union,” and he urged the IWW to use Flynn solely for the goal of recruiting more women organizers into the IWW.

When Flynn received her first letter from Hill in January 1915, she was an internationally and nationally recognized public figure. Her ten years work for the IWW had Flynn leading the historic free speech campaigns in Spokane, Washington, and Missoula, Montana, and organizing the great textile strikes in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912 and in Paterson, New Jersey, the following year.

Flynn for the OBU

Flynn was an exceptional high school student in the Bronx, and, much to the disappointment of her teachers and parents, when she was seventeen years old, Flynn left high school before she graduated to empower the disenfranchised into the IWW.

The IWW was the ideal choice for Flynn. A restless soul herself, Flynn enjoyed her life on the road with the Wobblies. The IWW, unlike the recently formed American Federation of Labor, IWW organizers were committed to their vision of OBU (One Big Union) and consistently practiced solidarity: “If you are a wage worker, you are welcome. . . . The IWW is not a white man’s union, not a black man’s union, not a red man’s union, but a workingman’s union.” The AF of L initially focused only on skilled labor workers and avoided women and people of color; the AF of L holding on to the incorrect premise that such workers could not be organized.

When Flynn was sixteen years old, she stepped up to the soapbox and delivered her first speech in Harlem, “What Socialism Will Do for Women.” Flynn possessed an innate brilliance and delivered her oratory easily. With her long black hair, petite frame and blue eyes, Flynn was a striking jawsmith and a vision to behold. Much to the dismay of the local politicians and the local law enforcement, who were always at the ready to squash any Wobbly assembly, wherever or whenever, Flynn stepped onto the soapbox. She drew the biggest crowds ready to hear her message of empowerment. Before long, the Los Angeles Times described her as a “leather-lunged hellion that breathed reddish flame,” and a “she-dog of anarchy.” By the time Flynn would step down from the soapbox, a Philadelphia reporter stated that “the perpetual inebriate forgot about the swinging doors” and “the corner loungers stood straight.” Flynn’s jawsmithing was legendary and remained one of her most effective organizing strategies.

Writing with The Rebel Girl

After Hill’s first letter to Flynn on January 18, 1915, they became regular correspondents. Hill was astounded by Flynn’s prodigious ability to perform a great many tasks within her days and complete them so competently. She was a full-time labor organizer as well as a divorced woman and single parent to a six-year old son. “Have been trying to figure out how you can have the time to write me such nice, fat letters and hold big meetings every night besides,” Hill wrote in a letter to Flynn in March, “but I guess you are like Tommy Edison, you don’t sleep more than four hours a day and work twenty.” In another letter, Hill imagined seeing Flynn “boil spuds, iron clothes, and sling ink all at the same time.”

After Hill’s first letter to Flynn on January 18, 1915, they became regular correspondents. Hill was astounded by Flynn’s prodigious ability to perform a great many tasks within her days and complete them so competently. She was a full-time labor organizer as well as a divorced woman and single parent to a six-year old son. “Have been trying to figure out how you can have the time to write me such nice, fat letters and hold big meetings every night besides,” Hill wrote in a letter to Flynn in March, “but I guess you are like Tommy Edison, you don’t sleep more than four hours a day and work twenty.” In another letter, Hill imagined seeing Flynn “boil spuds, iron clothes, and sling ink all at the same time.”

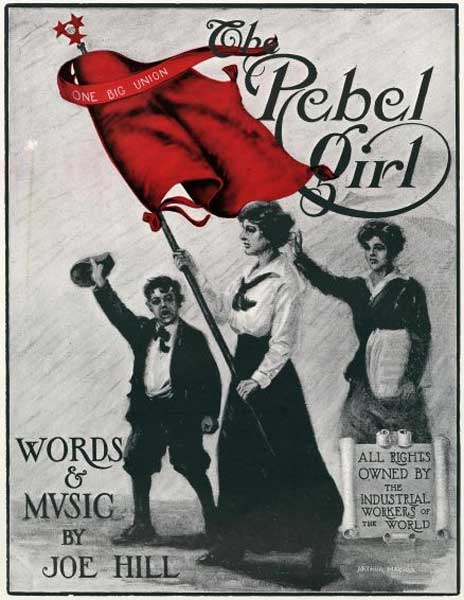

A month after his first letter to Flynn, Hill began to compose “The Rebel Girl” in appreciation of Flynn’s work and with the hope that the song would “help to line up the women workers in the OBU [One Big Union].” Hill would later acknowledge to Flynn that, given her great influence on him, when he composed the song, “you were right there and helped me all the time.”

Forty years later, Flynn would use the song’s title for her autobiography, The Rebel Girl.

A Visit with Joe Hill

In May 1915, the Rebel Girl Gurley Flynn was able to arrange a visit with Hill, when she would be lecturing on her first national tour since her son was born. It was an ambitious trip: Flynn would be lecturing in forty-seven cities over nineteen states, but it was her May 6th meeting with Hill that was her most anticipated stop.

Previous to meeting Hill, Flynn held some optimism that Hill would eventually be exonerated from this “crude frame-up” given the flimsiness of the evidence the state used to convict him.

The visit would be for only one hour, to be held in the sheriff’s office with others present. Flynn would be his first visitor since his sentencing. Writing about her visit with Hill in Solidarity magazine, Flynn was struck by the juxtaposition of the beauty of Salt Lake City’s streets “with its windswept streets. . . green shimmer, high altitude and clear pure air” against the rank odors of the “fetid jail odor,” cut by the “sickening smell of disinfectants.” They were denied even the smallest pretense of privacy.

It would prove to be their only visit. “He is tall, good looking, and naturally thin after sixteen months in a dark, narrow cell, with a corridor and another row of cells between him and daylight, and ‘nourished’ by the soup and bean diet of a prison,” Flynn wrote in Solidarity.

It would prove to be their only visit. “He is tall, good looking, and naturally thin after sixteen months in a dark, narrow cell, with a corridor and another row of cells between him and daylight, and ‘nourished’ by the soup and bean diet of a prison,” Flynn wrote in Solidarity.

Flynn called Hill a “free spirit” and “inimitable songster and poet of the IWW.” Flynn wrote of their meeting, “Let others write their stately Whitmanesque verse and lengthy, rhythmic narrative. Joe writes songs that sing, that lilt and laugh and sparkle, that kindle the fires of revolt, in the most crushed spirit and quicken the desire for fuller life in the most humble slave.”

Hill retained true to his characteristic trait of deflecting attention away from himself and had Flynn talk at length about the IWW’s progress. “And so the hour was spent in giving him the news of the movement,” she wrote. “I’ve seen men more worried about a six months’ sentence than Joe Hill apparently worries about his life. He only said: ‘I’m not afraid of death, but I’d like to be in the fight a little longer.’”

Flynn was noticeably shaken when their hour had nearly run itself through. She felt as though she was leaving a tomb and thought about Hill’s prospects when the state of Utah was determined to have Hill executed.

When they said their good-byes at the barred door, Hill pointed outside to “an expanse of a beautiful lawn” and attempted a joke about the brevity of his own life. “He’s lucky, Gurley. He’s a Mormon and he’s had two wives and I haven’t even had one yet.”

Fight for Freedom

Back in New York, Flynn worked with Big Bill Haywood in Chicago and IWW writer Ed Rowan in Salt Lake City on Hill’s appeal, to educate and agitate the people on the travesty of justice in Hill’s case. In the coming few months of Hill’s life, as he was becoming more of a symbol than a real man, and, noticing the rapid use of the IWW’s diminishing resources, Hill had urged the IWW through a letter to Flynn to have the IWW cut short their work on his behalf. Hill had wrote that it was senseless “to drain the resources of the whole organization and weaken it fighting strength just on account of one individual.”

While acknowledging Hill’s concerns, Flynn and hundreds of thousands of people would not allow themselves to let Hill remain a condemned man while they were able to fight for him.

Flynn remained his strongest champion. With only forty-eight hours before Hill’s execution date, she had presented Hill’s case to President Woodrow Wilson. Flynn had contacted friend and colleague Edith Cram, a Democrat of high social status and political connections—her husband was the “fixer” for the boss of New York’s Tammany Hall political machine. Cram and Flynn had been granted an interview with Wilson’s private secretary, Joseph P. Tumulty. The secretary had suggested a protocol-breaking plan of having the Swedish Prime Minister issue an appeal to Utah’s Governor Spry on behalf of its Swedish citizen, Joe Hill. He would also forward the appeal to the President himself.

That night, while Flynn and Cram were conferring about the case, the warden of the Utah State Penitentiary placed Hill under a death-watch after his announcement that preparations for the execution had been completed.

When the appeals from the Swedish Prime Minister Ekengreen and President Wilson went ignored by Utah’s Governor Spry, and, after a deluge of telegraphs to President Wilson, Flynn and Cram were given an audience with the President inside the Oval Office. Cram’s husband, John Sergeant Cram, and her brother-in-law, Gifford Pinchot, former chief of the U.S. Forest Service, accompanied them.

“The president greeted us cordially, in fact, he held Mrs. Cram’s hand,” Flynn recalled in The Rebel Girl. President Wilson listened “attentively” and recalled the failed intervention at the request of the Swedish Minister. Wilson wondered “if further insistence might do more harm than good.”

“But he’s sentenced to death,” Flynn interjected. “You can’t make it worse, Mr. President.”

Joe Hill’s Last Night

After the President’s final appeal to Governor Spry’s humanity was denied, Hill wrote again to Flynn, his humor and courage shining through as he faced death alone in his cell:

“Well Gurley I guess I am off for the great unknown. . . . They can kill me I know, but they can never make me ‘eat my own crow’. . . . I would like to kiss you Good-bye Gurley, not because you are a girl but because you are the original Rebel Girl.”

He also thanked Flynn for the photograph she had sent him of her son and told her of the song he had written for him. “You certainly have a right to be proud of your boy,” Hill wrote, “He’s got a forehead like old Shakespeare himself.”

Hill telegrammed Flynn on his last night:

“And now, good-bye Gurley dear. I have lived like a rebel and I shall die like a rebel.”

At ten pm, just before he fell into a heavy sleep, and, thinking that the bluntness of the telegram wasn’t enough, he wrote Flynn his last thoughts:

“I have been saying Good Bye now so much now that tit is becoming monotonous but I cannot help to send you a few more lines because you have been more to me than a Fellow Worker. You have been an inspiration and when I composed The Rebel Girl you was right there and helped me all the time. . . . With a warm handshake across the continent and a last fond Good-Bye to all I remain Yours as Ever.”

The next morning, Hill was executed. Hill’s invited visitors, Ed Rowan among them, were not given access inside the prison as Hill had requested. Hill’s visitors stood outside the prison walls and heard the firing squad carry out their orders.

Ed Rowan immediately telegraphed Flynn in New York:

“JOE HILL SHOT AT SUNRISE. HE DIED GAME.”

Nancy Snyder

Recording Secretary Emeritus, SEIU Local 1021

Are you interested in publishing your writing on Joe Hill? Write to us and let us know. We welcome your writing and artwork.